Supply Chain procurement is fairly unique in

the portfolio of goods and services categories purchased by industrial corporates. It is large, complex, and usually only

thoroughly practiced every 3 to 5 years – in the best of cases.

The Supply Chain Service Providers’ industry

is increasingly dominated by large players who control and command the assets,

the intellectual capital and the human resources, tilting the balance of power

their way... Effective spend of supply chain budgets therefore requires a

scarce combination of skills: a good

command of large B-to-B procurement processes and a good understanding of the

nuts and bolts of logistics.

Having managed multiple supply chain

procurement processes in different industries over the last 10 years, we have

identified some of the key factors that influence strategic interactions

between Principals and Suppliers, and the latest trends in South Africa and to

a lesser extent in the rest of the continent.

These trends can be exploited equally by parties on both sides of the

fence, and will become even more relevant as South Africa continues its current

slow growth trajectory with resulting cost containment, partly through

procurement squeeze.

These trends can be summarised along 4 main axes:

Context

Due to its size, supply chain spend should be

one of the procurement priorities within industrial/manufacturing companies:

§ Even when a

particular company’s policy calls for managing supply chains in-house, it will

nowadays invariably outsource some aspect of that supply chain (be it long term

vehicle leases, or long-haul bulk distribution).

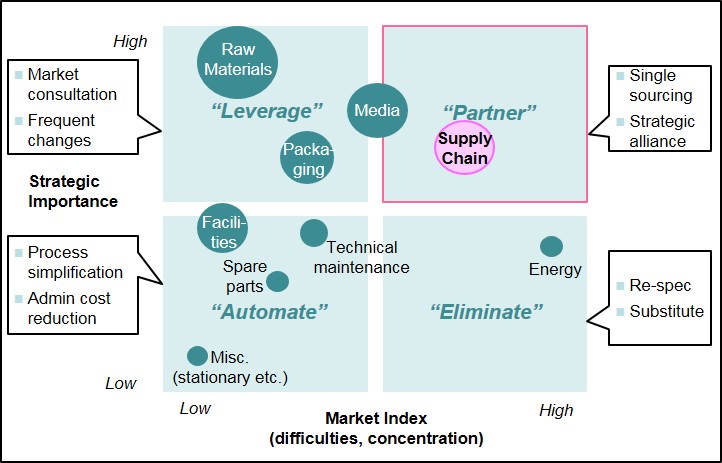

§ Supply chain is

in fact fairly unique in the traditional procurement matrix: it is one of the

few spend categories that is sizable, of high strategic importance to any

industrial company, especially to FMCG companies, and also has high levels of

supplier concentration, as shown in Figure 1.

§ Managing supply

chain spend requires a good understanding of both procurement processes and the nuts and bolts of

logistics. These competencies rarely sit within the same divisional structures,

but value for money is unlikely to be realised if input is missing from one of

the 2 disciplines.

§ However, purchasing reviews and contract

reallocations viewed from the standpoint of individual companies, generally

occur only every three to five years – a lifetime in the evolution of the South

African supply chain market!

§ We have identified some of the latest trends that

are driving negotiations between Principals and suppliers. Four such trends are

expanded below.

Figure 1: Example Category Spend Matrix

1.

“Justify

your ownership”

Ownership has historically revolved around the

single criteria of asset utilisation: If Principals could provide enough

utilisation within their operations, then they could own the assets – if not,

they had to rely on their suppliers to pool the utilisation of different

Principals.

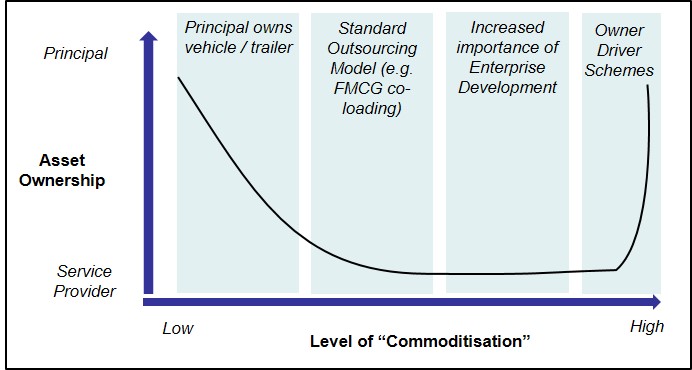

Traditional models of suppliers owning

vehicles are now changing, taking into account how commoditised the services

are.

For highly specialised services, Principals

prefer to own the assets, be it trailers or vehicles or loading equipment. This

serves a number of purposes:

§ Firstly, an

increasingly specialised service will result in a greater degree of asset

exclusivity in differentiating the offer. In other words, the Principal is less

likely to allow the asset to be used by its competitors.

§ Secondly, the

timing of the maintenance of the asset is often in the control of the

Principal.

§

Thirdly, and

most importantly, highly specialised services can lead to difficulty in

switching between service providers. Owning the assets can reduce lock-in and

ease the transition from incumbent to new provider. In terms of the procurement

matrix (see figure 1), it enables the movement of the category from right to

left, thereby moving the balance of power more in favour of the Principal.

For generic services, ownership tends to be

retained by the service provider. This is the case for traditional FMCG

companies where the service providers (under significant pressure due to

retailer DC centralisation) offer aggregator services to multiple Principals,

all of which require delivery at the back door of the traditional modern trade

outlets. In this instance, an individual Principal pays only a portion of the

service.

For highly commoditised services, Principals

are placing even more importance on enterprise development. In some cases (e.g.

Lafarge, ABI, SAB and more recently Adcock Ingram) commoditised services can be

outsourced via owner-driver schemes. Although the service is technically

outsourced, the funding mechanisms employed grants control of the vehicles to

the Principal, in substance if not form, as shown in Figure 2 (below).

The models have differing implications for

role players:

§

For service

providers, the onus is on proving their competence in the effective management

of the assets over their life.

§ For Principals, the key is to ensure retention of any proprietary aspects of the supply chain, ensuring that they are not unnecessarily tied in by long-term contracts and can therefore keep their providers “on their toes”.

Figure 2: Asset

Ownership Trends

2. “Price for service”

Principals and service providers are moving away from simple Fixed/Variable or Closed/Open-book models to more advanced pricing mechanisms that better reflect the risks and responsibilities of each party.

Client Example 1

The supplier is responsible for the management of

staff; therefore an aggregate hourly rate is agreed upon for staff cost per

route type (local milk run vs long haul) that includes a reasonable allocation

of overtime.

If the supplier fails to manage their staff allocation

correctly per route and run into unexpected overtime, this has to be absorbed

as part of the agreed upon blended normal and overtime rate.

In this way, the Principal is assured of quick turnaround and the supplier has every incentive to keep the working time equal to or even below the estimated cycle time.

Full open book (also referred to as “cost+”)

pricing leads to suppliers having little to no incentive to manage costs down

as they are all passed directly to the Principal – in fact the reverse

incentive is true as the supplier earns greater margin when the cost is higher.

Traditionally, Principals have overcome this

problem by enforcing a commitment to deliver savings – but the saving

commitment percentage is often a fairly arbitrary number, and it is almost

always difficult to measure (Did overall costs drop because my volume

decreased? Did my volume switch to more local deliveries, changing my

distribution mix? How did the unexpected fuel increases impact the overall

savings programme?)

Closed book or fixed pricing means that the supplier must build in

sufficient “fat” to protect itself from unexpected events such as delays in loading

etc. Consequently, Principals will not benefit from cost savings if they are

performing their roles better than the industry average.-

Leading companies recognise that pricing should be structured so as to

align the interests of both suppliers and Principals, and take into account the

allocation of responsibilities.

3. “Re-engineer your supply

chain”

At its core, supply chain services are about getting products from point

A to point B, reliably, within required SLAs and at the cheapest price. There

is however only so much margin that can be squeezed out of the rates of a

supplier before the offer becomes unsustainable.

Best in class companies know how to re-engineer the solution so as to

obtain the savings they require. In other words, it is not a pricing game

anymore, but rather a process reengineering matter, which requires Supply and

Demand considerations.

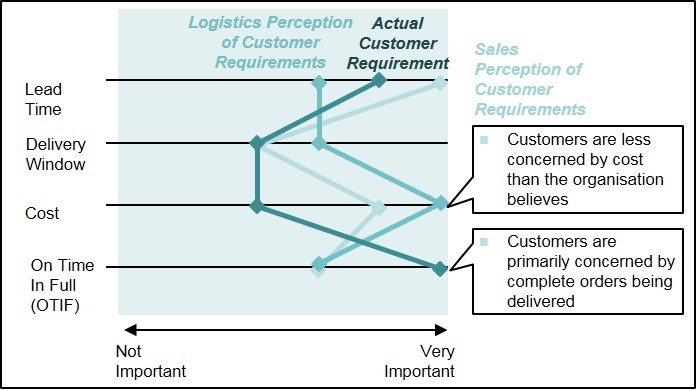

Conceptual Demand

While it is a tried and tested maxim in Customer Service in general, we

often find that companies are guilty of not understanding the importance of

specific KPIs to the end customer.

This leads

to over-delivery in areas that are less important to customers and under-delivery

in the areas that could be driving customer loyalty.

Principals can ensure they are not presenting an “over-specified” solution to meet

customer requirements, as shown in Figure 3 (below).

Client Example 2

The Principal believed that a next day delivery

promise “no matter what” would differentiate them in the market which was in

general accepting of long lead times. The implication of this service level was

that a new inland warehouse was required.

While both the customers interviewed and the sales

team had recollection of the multiple times an emergency order was required, an analysis of customer ordering

patterns revealed that only ± 10% of orders were made outside Nominated

Delivery Day (NDD) due to unforeseen emergencies.

This insight meant that inland customers could be serviced primarily from coastal depots, with minimal emergency stock being maintained for the exceptional next day delivery.

Figure 3: Matching Performance to Customer

Requirements

Figure 3: Matching Performance to Customer

Requirements

Conceptual Supply

One example of changing supply that frequently appears is the management

of return legs. The flow of freight across South Africa is heavily imbalanced.

If a vehicle is not able to secure backhaul volume, it returns empty. The

frequency with which this happens will be reflected in the rate that the

supplier is able to provide.

Client Example 3

The Principal required flexibility in fleet size to deal with the highly

cyclical nature of product demand. Instead of choosing a specific size of core

fleet and renting in additional vehicles to cover peak volume (at significant

cost), they made use of the existing spare capacity of supplier fleets.

This was done by including overall fleet size and operational set up as

a commodity in the tendering processes. Suppliers were requested to quote on

what proportion of vehicles in the core fleet could be “re-absorbed” should

they not be required in a given month.

Those suppliers that could effectively smooth the principal’s peak

demand requirements with their own demand cyclicality were best placed to

provide a competitive bid.

Traditionally this has meant that companies will either make use of

Freight Brokers, or alternatively request frequent updates to quoted rates to account for the changing contractual volumes obtained

by their suppliers. We have seen two emerging and divergent strategies which

companies employ to address this problem.

The first

strategy is to effectively bring the broking model in-house. This means

building the tools to allow a wide range of suppliers to continuously and

electronically bid on routes. It enables suppliers to accurately reflect their

own contractual economics. Thus, if a supplier is able to secure a two month

transport contract with a local farming cooperative shipping

product from Limpopo to Gauteng, they can afford to bid significantly cheaper

on Gauteng freight being transported to Limpopo. In theory, in-house broking

tools provide the most accurate market rates, without the broking margin

(provided the supplier base is sufficiently representative of the pool of

transporters operating in the region).

The second

strategy is to contractually place the risk of return loads onto the supplier

or consortium of suppliers. The strategy requires a good understanding of the

economics of both haulage and overall product flows across South Africa.

Effectively the tender process identifies the supplier (consortium) that has

the best “contractual balance” of return freight and locks them in to the

arrangement.

This arrangement can be highly beneficial to both parties:

§ Suppliers are provided with an opportunity to run back-to-back contracts

with a significant improvement in their asset utilisation levels.

§ Principals are able to ensure they benefit from the supplier synergies, and importantly that their competitors cannot!

4. “Read the fine print”

More impetus is being placed on this once neglected area of the

contracting process. The focus on the key cost metrics (rate cards, cost/km

etc.) during negotiations can often lead to savings in the first year of a

contract, that are quickly eroded when escalations begin to kick in. Fair

escalation mechanisms are critical in ensuring that a contract is extended

beyond the initial period.

·

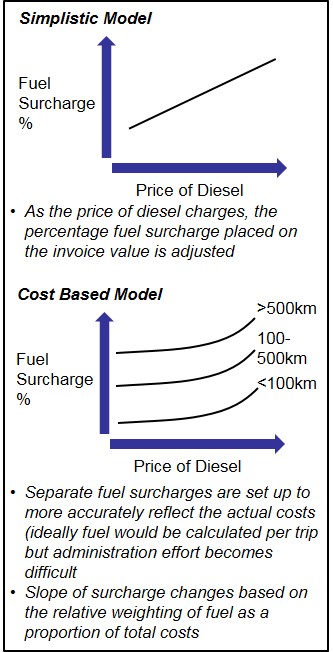

Fuel surcharges are often used to control

for monthly fluctuations in the price of diesel. Companies are moving away from

flat rate changes, taking into account the actual proportion of diesel cost per

element of the contract (i.e. short haul vs long haul), as shown in Figure 4.

·

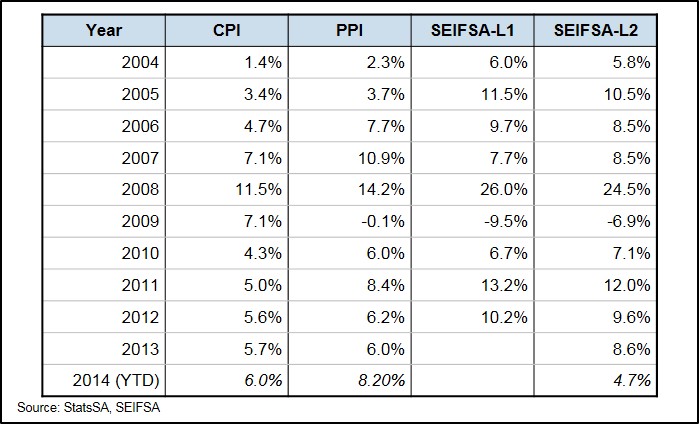

The selection of which index to use, as

well as what proportion of the contract will be linked to what index is also a

relevant topic. As can been seen by the variations in some of the major

indices, the selection of an escalation method can have a material impact on

the overall cost, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 4: Fuel Surcharges

Figure 5: Escalation Indices

The question of who bears the cost of fixed assets if a Force Majeure is declared is generally a

difficult topic and one settled by who holds the balance of power at the

negotiation table. It is important to know and state contractually what the

base fixed costs are, stripping out all variable costs and supplier profit.

These can also be based on the type of Force Majeure. For instance; in the case of a national transport strike, all salary and benefits related costs should not be included in the fixed cost base. In instances where all efforts have been made to continue operations but to no avail, the fairest distribution would be for both supplier and principal to share the contractually quantified fixed cost equally.

Conclusion

Logistics Procurement is confirmed to be a critical component of most

companies’ cost bases and is often chosen as a differentiating factor. One is likely to see further developments

along the 4 axes above as well as other dimensions of logistics services

procurement.

As the economy moves into a slow growth trajectory, one will see more

emphasis on cost containment on one side while customer service will still need

to be maintained and even improved on the other. Supply Chain procurement usually features as

a first port of call in such a context, and can certainly still provide

corporates with levers and opportunities for cost savings and service

improvements.

Contributed

by: Jean-Louis Hazard, Managing Director, Haute Performance