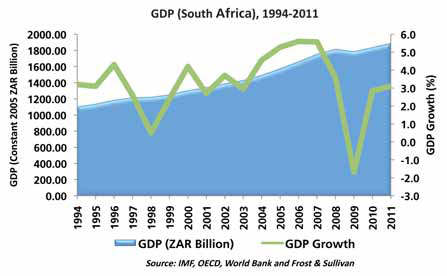

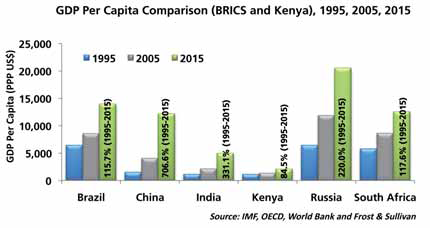

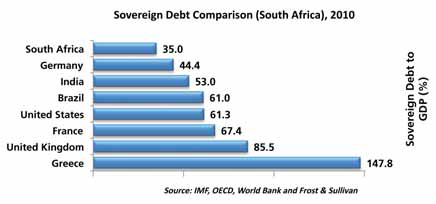

At the national, or macroeconomic level, South Africa’s response to the global recession of the past few years has been relatively good, as the graphs demonstrate. GDP growth increased sharply from 2003 to 2008, and much of South Africa’s GDP growth has been driven by consumption expenditure. The country’s GDP growth is expected to remain between 3.0 and 4.5 percent from 2011 to 2015, and consumption expenditure will grow at a greater rate in South Africa than in many developed economies. Our entry into the BRICS emerging market trade bloc allows for significant trade opportunities and growth opportunities on the back of the fastest growing economies in the world. It is estimated that by 2014 the BRICS economies will make up approximately 60% of the global economy.

A significant opportunity therefore exists for South African business. But it will need the right supply chain competitiveness to be able to take advantage of it. Where do South African businesses perceive their competitive advantages and constraints to lie?

Macroeconomic Overview

GDP Growth Comparisons

Drivers of Competitiveness

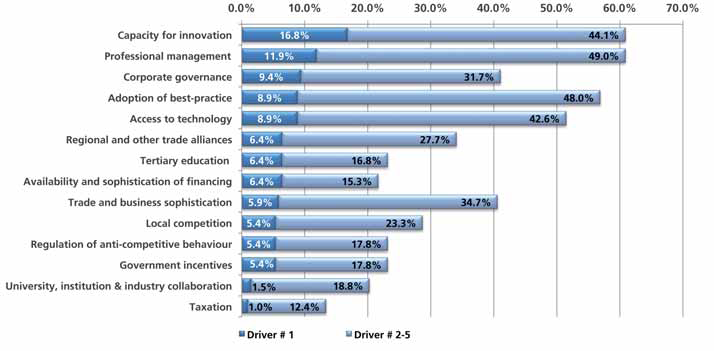

The major potential drivers of South Africa’s corporate competitiveness, according to our respondents, reflect the relative sophistication of the South African economy. The top arena in which we can compete internationally is our ‘capacity for innovation’, followed closely by ‘professional management’, ‘adoption of best practices’ and ‘access to technology’. These strategic management factors all represent distinct potential advantages, especially in and emerging market context, and, properly applied, make South Africa an attractive investment and trade destination.

Constraints on Competitiveness

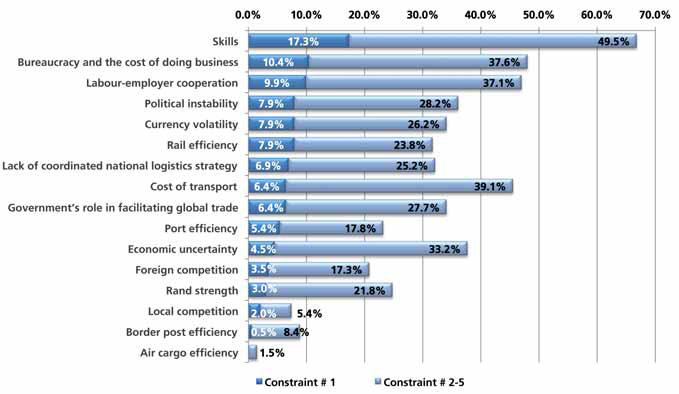

Turning to the constraints on the competitiveness of South African businesses, the runaway biggest obstacle to growth and competitiveness is the skills vacuum, followed by bureaucracy and the cost of doing business, labour-employer co-operation and the cost of transport. These obviously closely align to the business and supply chain constraints listed earlier, but it is interesting that the skills vacuum has moved so clearly to the top of the agenda.

It indicates the respondent’s awareness that the country’s longer-term possibility of success in a more competitive emerging economy landscape is not linked to cost reduction or even increased supply chain effectiveness, but on the quality of the country’s people and their ability to keep on offering the qualities that make the country competitive, such as the ability to innovate and manage businesses professionally and in line with global best practice.

Sector Competitiveness

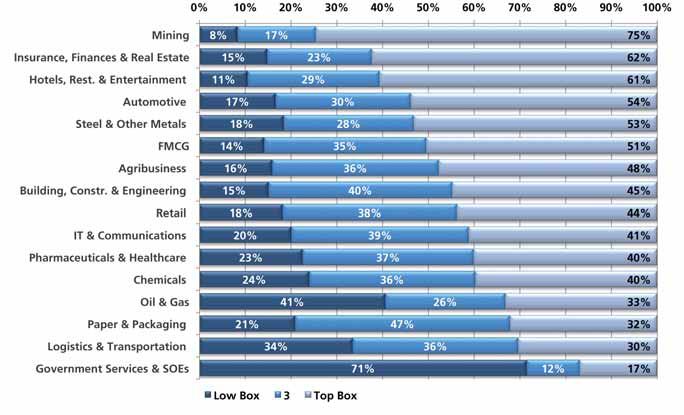

In delving further into the competitiveness issue, we wanted to establish which sectors of the South African economy are seen as having unique competitive advantages and why.

The Mining sector, the traditional powerhouse of the economy, retains top spot here. This is presumably by virtue of South Africa continuing to have a strong export flow of commodity resources, but despite the gradual decline in the local Mining industry relative to international competition. Other industry sectors seen as offering the country competitive advantage tend to be those in the services sector where we have relatively sophisticated offerings in an emerging market context, such as Financial Services and Tourism. In the increasing growth of the Services sector we are following many other emerging market economies, especially in Africa, where traditional sectors such as Agriculture have declined, and the Services and Tourism sectors have grown – rather bypassing the manufacturing part of the developed world’s historical route from agriculture and food production, via manufacturing to services.

Industry Sector Representation

and the Skills Vacuum

As part of our efforts to gauge the market’s opinion about how individual industries can become more competitive, we wanted to find out about the perception of how each industry sector is organised formally to lobby and to develop skills and other strategies for growth, as well as how it represents itself to Government.

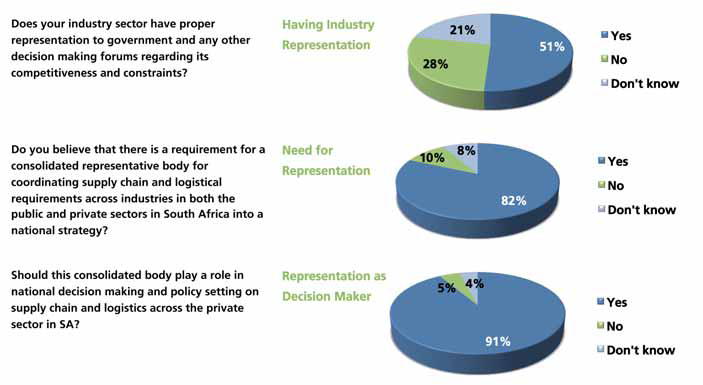

Industry Representation

Surprisingly, only about half of all industry sectors in the sample definitely have industry representation. A far greater number, over 80%, feel there is a need for such representation, and of those, 91% feel that such a consolidated industry representative body should lobby with government at a national strategic decision making level.

While this view may be unsurprising, the next graph demonstrates that there is a clear need for such a representative body that aligns strongly to where respondents feel that constraints exist on the growth of their businesses and their supply chains in particular.

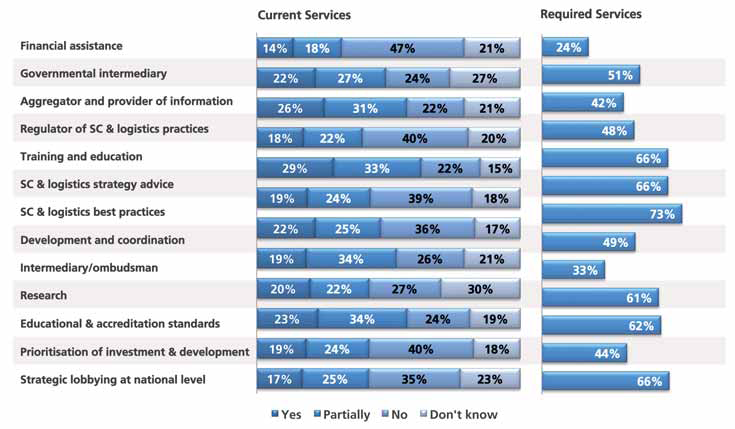

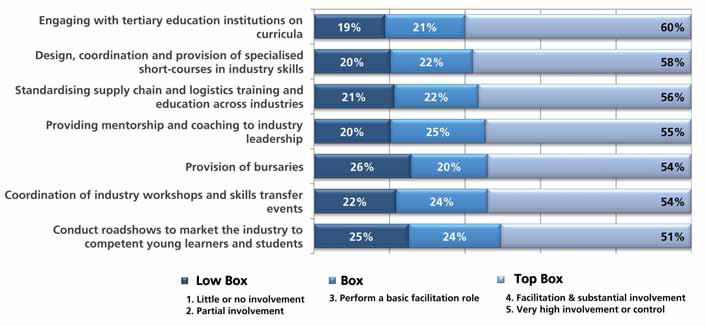

Functions of Representative Body

Areas where the services of such an industry body are felt to be required include the co-ordination and alignment of training, education and skills support, as well as areas such as applying industry best practices and strategy advice and support. In terms of how the market sees the alignment of professional training with formal education, over half believe there to be alignment between training and education in the supply chain field, and what skills are required by the market.

Aligning Professional Training with Formal Education

Thus, despite the unanimous view on a general skills deficiency, there is at least a degree of usefulness for formal qualifications in businesses. Many respondents believe this can be improved by further engagement between the private sector and tertiary institutions on what is needed from their curricula.

For the full report, please visit www.supplychainforesight.co.za